Optimistic we are on this the second evening of the donkey phase, despite the setbacks. I can’t speak for Ayelen on this but only before the very start of this trip did I wonder which would be the easier to handle between a camel and two donkeys. As soon as we’d had time to get used to our Bactrian camel it was clear that she was going to be a dream compared to two of a species renowned for it’s simple-minded and irrational obstinacy. Yet even now I still nurse the presumption that I can do it better than others, that I have a certain ‘way’ with animals and that within a day or two we’ll have these two little jennies going in a straight line and at more than 2kmph without having to beat the crap out of them.

This belief is supported by such useful websites as that of the Donkey Sanctuary in the UK. No donkeys have the crap beaten out of them in the Donkey Sanctuary. One must take the time to learn what makes them tick, what scares them and why and one must familiarise oneself with the various proverbial carrots on sticks.

Using this violence free approach we just make it out of town before the elder of the two has shed her load and escaped. Mellis and Tolkonbek, the men who sold us these monsters, advised having one of us in front leading the older animal, the younger one tied to the older’s load and the other of us bringing up the rear. The younger one overtakes the other then veers across her front, upsetting both loads. This scares both animals who then accelerate off the road, towing me in their wake. Ayelen tries to head them off and grab the younger one’s halter and we all end up in a kind of Larson-esque jacknife situation with passing drivers slowing down for a good laugh. Among them are Mellis and Tolkonbek who have been on a huge bender since offloading their most useless animals onto two hapless tourists for double the normal price. They shout good-humoured advice at us before swerving away, barely able to steer through the vodka haze and belly laughs. We are laughing too because it IS comedy and I only wish there was somebody else to film us. Neither of us can make the donkeys move at all on our own and the camera is missing it all.

We’ve set ourselves the task of getting from here, the very small town of Kochkor, to the ancient caravanserai of Tash Rabat and then finally to the village of At-Bashi – to sell the donks – in the next 22 days. On the map covering the wall of a local tourist service it looks to be around 370kms and will feature four mountain passes, three of which are over 3000m and probably still a wee bit snow covered. Where the ground is good and relatively level we need to be covering 20kms a day or we’re not going to make it. That’s not a lot to ask, but in  the last two days we’ve done about 7kms. Admittedly the first day was largely spent manufacturing our tack; sewing a couple of old hessian sacks into a very stylish set of saddlebags in which to carry food, and converting some webbing straps into halters. The older of the two (left) carries our rucksacks, tent and tripod while the younger (below) carries food and cooking equipment. I’m happy neither of the loads are excessive and that in fact we have good animals. After a morning looking at various shabby and uncooperative beasts we found a herd of six from which I was allowed to choose whichever I wanted. Mellis and Tolkonbek looked on, agog with unconcealed delight.

the last two days we’ve done about 7kms. Admittedly the first day was largely spent manufacturing our tack; sewing a couple of old hessian sacks into a very stylish set of saddlebags in which to carry food, and converting some webbing straps into halters. The older of the two (left) carries our rucksacks, tent and tripod while the younger (below) carries food and cooking equipment. I’m happy neither of the loads are excessive and that in fact we have good animals. After a morning looking at various shabby and uncooperative beasts we found a herd of six from which I was allowed to choose whichever I wanted. Mellis and Tolkonbek looked on, agog with unconcealed delight.

Donkeys here appear to be worth so little normally that they are only kept at all to entertain children as yet too small for horses and to swap for a bottle of vodka in an emergency. The only reason they fetch slightly more right now is that there are Chinese road-building gangs dotted along the main road to Bishkek and they like to eat donkeys. We have agreed the equivalent of US$60  each and in their heads both men are already rehearsing the vodka toasts to come. After paying $2000 for a camel we are delighted with the price but I take my time choosing. Educated by various websites I base my decision solely on age and body condition and we have two girls, of five and seven years, both in good shape with no sign of being under-weight. The younger one has a very sweet face and enjoys nibbling my hand while the older has heavy eyebrows that give her an expression of unwavering disapproval. Hopefully they’ll get publishable names soon enough.

each and in their heads both men are already rehearsing the vodka toasts to come. After paying $2000 for a camel we are delighted with the price but I take my time choosing. Educated by various websites I base my decision solely on age and body condition and we have two girls, of five and seven years, both in good shape with no sign of being under-weight. The younger one has a very sweet face and enjoys nibbling my hand while the older has heavy eyebrows that give her an expression of unwavering disapproval. Hopefully they’ll get publishable names soon enough.

At least the campsites these first two nights have made up for any animal-related woes. Without any effort at all we’ve found poster-worthy spots that make our campsites in China look like the dungeons of hell: perfectly  manicured grassy banks along a clear river twisting through trees in spring green with snow-capped mountains in the background. Best of all, there are no police. Instead we have herds of horses with their young. There’s something about a riderless cantering horse that personifies freedom like no other image. Their muscular grace makes me catch my breath. Then I glance at at our funny little hobbit creatures and want to sob. Although they seem to outnumber people in these parts, horses cost between US$1-2k, due in the main part to their meat being considered a delicacy. We would still need two of them to carry our kit for 7-8hrs a day and we’d still be walking ourselves. In any case we’ve spent the camel sale proceeds on carpets to sell in Europe to offset the cost of this trip. As usual it’s disappointing to be poor and more so here where our poverty is mistaken for stupidity. The young herders, usually around 12 years old, for whom a horse is just one of those things in life, cannot understand why we are walking beside two donkeys and the look behind their manly handshakes is generally one of stupified pity.

manicured grassy banks along a clear river twisting through trees in spring green with snow-capped mountains in the background. Best of all, there are no police. Instead we have herds of horses with their young. There’s something about a riderless cantering horse that personifies freedom like no other image. Their muscular grace makes me catch my breath. Then I glance at at our funny little hobbit creatures and want to sob. Although they seem to outnumber people in these parts, horses cost between US$1-2k, due in the main part to their meat being considered a delicacy. We would still need two of them to carry our kit for 7-8hrs a day and we’d still be walking ourselves. In any case we’ve spent the camel sale proceeds on carpets to sell in Europe to offset the cost of this trip. As usual it’s disappointing to be poor and more so here where our poverty is mistaken for stupidity. The young herders, usually around 12 years old, for whom a horse is just one of those things in life, cannot understand why we are walking beside two donkeys and the look behind their manly handshakes is generally one of stupified pity.

Day three now and things are worse. We’ve sorted out the younger donk. It was just a case of letting her go; she’s happy to follow along behind. The problem is the older of our two, Grumpy Tosca – the latter half of her new name is Spanish for obstinate. She refuses to go at more than amble speed. It’s the same agonising rate of progress enjoyed by the Christmas shoppers blocking pavements in November and with several hundred kilometres yet to cover I cannot handle it. I’d love to be able to claim after all this that we did it without ever striking our animals but I’d be lying. But we do try every alternative and many seem to work at first. If I walk just behind Tosca with a stick swishing about in her peripheral vision, for example, she goes quite well for an hour or so, until she starts to wonder whether or not I am too wet to actually hit her with it and slows again to shopping pace. Then I add some suitable sounding cries and she gears up again for a short while. We swap the donks around but Tosca does not share the other’s lack of confidence and wanders off to eat. She must know what a whip means but is happy to forget. After a few hours I can see no way forward but to refresh her memory and am flogging her rump left and right with a short length of braided plastic cord and crying out “hup” and “drrrrrr” in the most forceful manner I can muster. By mid afternoon I think my voice cannot last another hour but we have moved some distance. My gaze is fixed upon the rope connecting Ayelen’s hand to Tosca’s halter. Whenever it tightens she gets either the lash or a shout. I try to make it a lesson so that only when she fails to react to the shout do I hit her. It’s exhausting and demoralising and part of me wants to give up already. I hate hitting animals and if this is to be our daily routine then I’d rather be at home. Despite my efforts Ayelen has dragged Tosca along all day.

At least the younger one, Little Scheister, is now trouble free; she simply follows behind stopping occasionally to eat then trotting to catch up again. She only earns her name when having fallen too far behind she canters to catch up and her load falls off. Spooked by the falling bags the little scheister puts down her head and runs for all she’s worth. Unfortunately I have wrapped her halter rope around the load so that it now grips the saddlebags rather than releasing them. The little fool thinks she is being pursued by some bouncing savage beast, without legs but nonetheless tenacious in the chase. Sadly I don’t think to whip out the camera. I only join Ayelen in gawping helplessly as she gallops around and around us in a wide circle, methodically shredding our beautifully stitched saddlebags on the stony ground. I hate donkeys at this stage and feel a powerful urge to inflict real damage upon them. My braided cord is clearly almost completely ineffective through Tosca’s thick and coarse hair and late in the day I pick up a length of broken fan belt. I’ll attach it to the end of my stick tomorrow and methodically flog her to death with it.

falls off. Spooked by the falling bags the little scheister puts down her head and runs for all she’s worth. Unfortunately I have wrapped her halter rope around the load so that it now grips the saddlebags rather than releasing them. The little fool thinks she is being pursued by some bouncing savage beast, without legs but nonetheless tenacious in the chase. Sadly I don’t think to whip out the camera. I only join Ayelen in gawping helplessly as she gallops around and around us in a wide circle, methodically shredding our beautifully stitched saddlebags on the stony ground. I hate donkeys at this stage and feel a powerful urge to inflict real damage upon them. My braided cord is clearly almost completely ineffective through Tosca’s thick and coarse hair and late in the day I pick up a length of broken fan belt. I’ll attach it to the end of my stick tomorrow and methodically flog her to death with it.

But I never do so, for in the morning Tosca seems to have made a decision. She walks all day without my hitting her once. I only have to yell out occasionally. It’s not the brisk pace we managed with our camel but it`s a speed I can get used to. Approaching the Kyzart pass and still shadowing the road, we know from the kilometre markers that we are managing 4kmph, which is OK. The difference it makes to our mood is enormous and I like to think the donks feel the relief also. I can even feel content that we’ve achieved this without actually inflicting any physical pain, for in the night a male donkey wandering free comes along to roger Little Scheister senseless. She must be in season for Tosca is ignored. After several hours of periodic rape I am worried my load carrier will get no sleep at all so attempt to beat off her admirer with an escalating range of weaponry that culminates in a large rock hurled at his ribcage. He shows not a flicker of discomfort so I fall asleep with an easy conscience over Tosca’s rump. Ayelen stays awake, enthralled by Little Scheister’s gameplay outside the tent, alternately provocative then defensive. In the morning all my girls are knackered but between coaxing them all along I get to listen to a fascinating hypothesis on sexual phsychology across the animal and human kingdoms.

The 2664m Kyzart pass presents no difficulties but we’re about to get higher as we cut south towards the mountain lake of Song Kul. We try to stock up for the coming week in the village/town of Kyzyl Emyek and meet with the next of our problems. In what is to become a recurring disappointment we find that every little shop stocks little but vodka, biscuits and a selection of cheap earrings and other trinkets. This is presumably a winning formula forged during the Soviet years or perhaps in the economic depression that followed them: vodka for him, biscuits and sweets to keep the kids diverted while he beats up her and then jewelry to make everything better in the morning.

Between beatings she must be fairly flat out in the kitchen and garden for there is no butter, cheese, milk, yoghurt, jam or even bread for sale. We find ourselves in buoyant mood if we’ve managed to buy a kilo of carrots and from hereonin are forced to make our own bread over an open fire, sometimes in a snowstorm. At least shopping is rarely a dull experience; there’s a steady stream of drunken men of all ages arriving at each shop in beaten up old cars and all want to chat. There’s not much sign of employment around but nor is there of poverty, outwardly at least and excepting the rampant alcoholism. Elaborately dressed schoolgirls wander back and forth past neat little houses and boys show off their bikes. But almost every car, no matter how old, sports a taxi sign in the window and gangs of them prowl the streets looking for a fare. It’s a pastoral economy and the winters are long and boring. These people are semi nomadic and live for the moment in June when the grass at 3000m is long enough to support their flocks and they can decamp en masse to the summer pastures or jailoos. Up in the mountains under the summer sun life is good and wholesome, the yurts busy with children and laughter, and growing piles of empty vodka bottles glint in the sunlight.

But right now is a touch early for all that and whilst we’ve seen a few yurts being assembled at around the 2500m mark the men here tell us there are only fishermen up at Song Kul. I am worried about the amount of grass there for our donks but all assure me there is plenty. They have a peculiar signal for ‘plenty’, drawing the forefinger around the throat as in a jugular-cutting motion. At first I take this to mean that our big-eared bag-carriers will be stuffed if we take them up there so early in the year but with a bit more probing it seems they’ll be OK if we give them a good 8hrs a day of unhindered grazing.

Kyrgyzstani, like Uighur, is a Turkic language but there are enough differences between the two for Ayelen and me to feel that we are almost starting again. Unlike those in rural Xinjiang however, the people here are very willing to talk and will make a beeline for us straight away. Most think we are Russian at first and that there must be a back up car and a guide somewhere near. An old man empties his pockets of walnuts for us, a tractor driver gives us his bottle of fermented mares milk, a woman invites us to her home to stay the night. We refuse the latter – it’s too early in the day – but revel in their support and friendship. In a single hour there is more hospitality shown to us here than in the entire two months in China. I cannot, right now, think of a more damning indictment of communism.

With nine out of ten people agreeing to the location of the Tuz Ashoo pass and Little Scheister freshly loaded with carrots, flour, a very passable sausage and a bottle of vodka, we head south to intersect the Kyzart river and camp. At 3300m the Tuz Ashoo will be one of the highest obstacles in our way and we try to get away before our usual 10am start. I want to cross with enough time in the day remaining for us to descend on the other side and find grass but it’s the donkeys, grazing freely, who thwart this plan. Choosing instead to follow somebody’s cattle they vanish over a hill as we are cooking flatbreads on the last firewood we are likely to see for a week or more. Later, a wrong turn leads us up the wrong valley and we have to cross a very steep spur to get back on track, losing another hour. At least the mistake affords us the only glimpse we are to get of the rare Siberian goat; four of them sprint away above us. We argue noisily over which way to go, both wanting to lead. It’s the same thing wherever we go; we have never chosen the same route, whether it’s crossing a train station to a  certain platform or navigating a crowded street. One might think, therefore, that we’d be used to it by now but for some reason the annoyance felt each time is wonderfully fresh. This time it’s Ayelen’s turn to have been obstinate, bloody-minded, useless and wrong. She’s still getting an earful for it when a nearby boulder morphs into a well-fed shepherd wearing shades who steps forward to offer her a bunch of Edelweiss. This lifts the mood mightily.

certain platform or navigating a crowded street. One might think, therefore, that we’d be used to it by now but for some reason the annoyance felt each time is wonderfully fresh. This time it’s Ayelen’s turn to have been obstinate, bloody-minded, useless and wrong. She’s still getting an earful for it when a nearby boulder morphs into a well-fed shepherd wearing shades who steps forward to offer her a bunch of Edelweiss. This lifts the mood mightily.

It’s past four when the switchback dirt track we are following disappears under snow just a hundred metres shy of the summit. Someone’s already been over on a horse and there’s a narrow path of compressed snow and ice to follow. However, for some reason best known to them and their annoying species the donks won’t stay on it. Donkeys’ hooves are very small and while Ayelen and I can walk on the crust they sink straight in up to their bellies, shed their loads then refuse to co-operate at all. There’s no way around and we’re not turning back. I’m reminded of those old adventure films where a pack animal or two is inevitably lost into the river far below, and of the 19th Century expeditions through these parts where literally thousands of animals did actually perish in sudden onsets of winter. We’re not facing such ruination but it’s cold, clouds are gathering and there’s nothing for them to eat at this altitude, nor any flat ground on which to put a tent. As if to highlight the situation there’s a brief flurry of snow and I get out my donkey communicator, unused for days, to read them the riot act.

I don’t know why but I hadn’t once considered that the lake of Song Kul would still be frozen over. As we crest Tuz Ashoo I am completely taken aback at the scene ahead. Several miles still ahead of us and 300m lower down lies this enormous flat plain of dazzling white surrounded by mountains. At it’s narrowest point the lake is about 18kms or 11 miles across, a monster. I try to take a picture but the camera can’t cope with it all.

I don’t know why but I hadn’t once considered that the lake of Song Kul would still be frozen over. As we crest Tuz Ashoo I am completely taken aback at the scene ahead. Several miles still ahead of us and 300m lower down lies this enormous flat plain of dazzling white surrounded by mountains. At it’s narrowest point the lake is about 18kms or 11 miles across, a monster. I try to take a picture but the camera can’t cope with it all.

In fact it’s one of the last photographs our camera takes. Presumably due to the dust of Xinjiang it’s little fan has been sucking in for several months pretty much all functionality has now been lost: focus (both manual and auto at anything other than infinity, so I cannot zoom), white balance, stills capture from movie (which means few photos for this blog), playback, a host of other less important features and now stills as well. In modern parlance, it’s fecked, but it’s still shooting film and recording sound. I find myself talking to it, begging it to live just a little longer. I think I need to go home.

We pitch camp in a hailstorm and cook bread the next morning in a snowstorm. A man passing on a horse laden with fish stops to say hello and following the shoreline later on we pass several yurts. Some have 4x4s  parked nearby. Everyone is out on the ice, little specks wandering from one fishing hole to the next. We want to go out there and see what they’re up to but they are using boats to navigate the 3-4m of open water between the shore and the melting ice and we can’t tell if they’re also using snow shoes or something to spread the load. The thought of a plunge puts us off and we keep going.

parked nearby. Everyone is out on the ice, little specks wandering from one fishing hole to the next. We want to go out there and see what they’re up to but they are using boats to navigate the 3-4m of open water between the shore and the melting ice and we can’t tell if they’re also using snow shoes or something to spread the load. The thought of a plunge puts us off and we keep going.

It’s an extrordinary day of wandering snowstorms. Appearing as great columns of mist, they seem to be waltzing around the lake and miraculously we weave among them unscathed. Just in front one drops it’s load and the ground turns white. By the time we get there the sun is out, the ochre grass is returning already and the column of falling snow is off to our right, but there’s another one coming in from the left and one behind too. The conditions veer  from freezing, biting wind to warm sunshine in less than a minute and we go from hoods and balaclavas to shirt sleeves and back several times every hour. I think it’s the first time I’ve had a hot sun on my face and snowflakes settling on my hair at the same time. Eventually, of course, our luck runs out and we get properly dumped on. The donkeys soon have white hats and the fat flakes melt into our worn-out waterproofs as soon as they settle. As if in payback for our earlier luck this storm sticks to us and follows.

from freezing, biting wind to warm sunshine in less than a minute and we go from hoods and balaclavas to shirt sleeves and back several times every hour. I think it’s the first time I’ve had a hot sun on my face and snowflakes settling on my hair at the same time. Eventually, of course, our luck runs out and we get properly dumped on. The donkeys soon have white hats and the fat flakes melt into our worn-out waterproofs as soon as they settle. As if in payback for our earlier luck this storm sticks to us and follows.

Without difficulty I can sense the misery of my three girls and scour the barren landscape for shelter. We are about to enter a huge, flat plain at the western edge of the lake and I want to stay put behind the last available ridge. But Ayelen reckons she spotted a hut several miles in front before the snow started so we press on hoping for a warm welcome and a dung-burning stove. The brain’s inability to discern accurate dimensions when faced with more space than it’s used to seeing, or ice chrystals in the air, or the two together, is a phenomenon I’ve come across before. Forty days into mushing dogs across Greenland once, my friends and I could see what looked like quite large buildings way up ahead, with people milling about them. Despite the improbability of this I became almost convinced that we were approaching a hotel. When we got there it was a small bird dead in the snow, nothing more, simply the only dark object apart from ourselves in a vast white space without discernable boundaries. As we get closer to it, Ayelen’s hut, so full of similar promise, turns into a wooden toilet, a cludgie. Somewhere beneath the snow around it will be the circular mark left by a summer yurt and somewhere else the ubiquitous pile of empty vodka bottles. It’s a bitter disappointment. We keep walking. Later she spots another hut. She says it has wheels but all I can see is another cludgie. This time, however, she’s redeemed: it’s one of the converted railway carriages that litter the former Soviet Union (main picture), dragged here years ago and used only in the  summertime. The door’s locked but just as we’re about to set up the tent in it’s lee a 4×4 rolls up with two men and a woman inside and great sackfuls of fish. They smash the padlock and insist we stay inside then give us six fish and drive off to the west where there’s another pass. The evening sun melts the snow, the donkeys get their grass and we retire inside to fry fish. We’re really loving our Kyrgyzstani camping scene.

summertime. The door’s locked but just as we’re about to set up the tent in it’s lee a 4×4 rolls up with two men and a woman inside and great sackfuls of fish. They smash the padlock and insist we stay inside then give us six fish and drive off to the west where there’s another pass. The evening sun melts the snow, the donkeys get their grass and we retire inside to fry fish. We’re really loving our Kyrgyzstani camping scene.

Another blizzard the following day covers over the track I know we should follow to get out of this mountainous bowl and in the whiteout we find and follow another. I haven’t jotted down enough detail in my notebook to know yet how far we’ve gone wrong, I’m only happy to lose some altitude. Arriving suddenly in a stunning little valley full of grass that’s longer and greener than they’ve seen since last year, the donks mutiny. My wife’s on the point of mutiny too so I maintain control by announcing that we’ll camp. There’s even a cave that I can tie the animals up in for the night.

It’s unusual to find such long grass in this country. Over-grazing is a huge problem in Kyrgyzstan.  The amount of livestock the land has to support has more than quadrupled in the last century, driving out the native fauna and their predators and causing widespread erosion. Flocks of over a thousand animals move over the landscape like locusts, trimming every blade to the ground, over and over again.

The amount of livestock the land has to support has more than quadrupled in the last century, driving out the native fauna and their predators and causing widespread erosion. Flocks of over a thousand animals move over the landscape like locusts, trimming every blade to the ground, over and over again.

Long grass can only mean one thing at this time of year: that there’s limited access to this valley from below. I don’t realise this at the time, of course, and instead congratulate myself for getting us lost and thus finding this little paradise. In the morning we decide not to follow the stream downhill as it vanishes into a precipitous looking gorge. Following animal trails we climb over a few spurs instead and descend again, entering another postcard perfect valley, this time trimmed with huge fir trees and wild flowers. It’s all too beautiful and there’s not a soul to be seen anywhere, nor even a goat. I just keep on missing those telltale signs, but at last one of them registers.

While Ayelen knocks up a cabbage, carrot and sardine salad I walk ahead to scout the rather ominous pile of house-sized boulders blocking the lower end of the valley. I find one of those geographical anomalies that might be described as a stupendous upheaval. Rather than glacier-carved this particular valley looks to have been rent apart, the resulting gorge too unstable for gravity and still crumbling thousands of years later. It’s a mess, as if God has been making all this in Lego and was called away to lunch. The donks won’t so much break their legs amongst the boulders as disappear altogether. To keep descending there’s only one other possibility and that’s another animal trail disappearing into the trees halfway up the valley. I follow this for a kilometre or so, contouring around steep grassy slopes between outcrops of fir until arriving on a ledge from which all becomes clear. Oh dear, very pretty but the girls are not going to like this! But it is possible, even if Ayelen and I have to ferry the loads down ourselves. The livestock trail switchbacks down a very, very steep and rocky slope sandwiched between cliffs and the scree of an active rockfall. Even as I arrive there are boulders performing a kind of Dambusters bounce down into the trees below, the accompanying sound like sporadic artillery fire. Beyond that, some 800m beneath my feet I can see the roofs of two converted railway carriages painted bright green amongst the trees. I’ve seen little evidence so far that Kyrgyz are into maintenance activities such as painting; these look official, like park ranger huts. At any rate there must be a track from there out of the mountains. On the way back I pick flowers with which to break the news of the toil to come.

It takes us the rest of the day to get down and at the bottom we are just in time to catch some men who unlock one of the huts for us before leaving. They express surprise that wolves haven’t attacked us. Inside is a woodstove and we are properly warm for the first time in weeks. Unwittingly we have ended up in Karatal Japaryk Reserve, which centres on this outstandingly beautiful and impressive valley. There are signs that this is one of those reserves where the proleteriat are kept out so that the well-heeled can come and shoot the protected animals, but looking up at the cliffs and the trees clinging to them I feel I can almost see a snow leopard or brown bear still clinging on.

Getting lost is almost an old fashioned concept in these days of GPS but it still serves Ayelen and me very well. Not having a map in a strange land is an interesting experience. In many ways it’s life, is it not? Technically, having no map, we are lost all the time on this trip, except for those moments when we arrive in a village and can name our position. We do know where we are trying to get to but it’s only the journey that’s of real interest to us. The journey is the goal. Our destination in this case, Tash Rabat, is just an old building and the end point it represents to us. I’ve made relatively detailed notes on how to get to it but only as much as we need in order to ask non-leading questions of the shepherds we meet along the way. “What’s the name of that river over there?” “Where is the horse trail to Orto Syrt?” We are reliant upon such titbits of information to reach our destination in the time allotted but we don’t need them to reach our goal. To reach that, we are better served by getting lost. It’s a fact: dealing with the unexpected is simply more challenging and interesting. We can feel as if we’re exploring rather than just travelling.

My notes therefore only need to contain enough detail to help us recognise the good titbits from the bad and sometimes we don’t need them at all. Sometimes the countenance of the fellow before us says it all. We go wrong again a few days later, having crossed the Naryn Valley. Ahead is another range of mountains to cross and we think we’ve missed the right path and have come too far to the east. Facing a long walk back down the mountainside I have only just said to Ayelen that we must ask our guardian angels to provide a really useful shepherd when a gangly, gap-toothed youth in his late teens appears astride a heavily pregnant donkey. Ayelen and I roll our eyes at each other; they’ve provided the very opposite. His younger brother, astride a baby donkey whose behind has been whipped raw, is as little help. Amidst their excited gabble – they won’t shut up – we decide on our own to go back and search again for a path, but then encounter their father on a horse. He’s drunk but at least points out the gorge we must enter. He says that it’s very steep in there and leaps off his mount to start re-doing Little Scheister’s load. A scuffle ensues. He is hard to deter but I don’t care how many donkey’s he’s packed; I‘m not about to take a lesson in loading from a man who allows his sons to so maltreat their own animals.

wrong again a few days later, having crossed the Naryn Valley. Ahead is another range of mountains to cross and we think we’ve missed the right path and have come too far to the east. Facing a long walk back down the mountainside I have only just said to Ayelen that we must ask our guardian angels to provide a really useful shepherd when a gangly, gap-toothed youth in his late teens appears astride a heavily pregnant donkey. Ayelen and I roll our eyes at each other; they’ve provided the very opposite. His younger brother, astride a baby donkey whose behind has been whipped raw, is as little help. Amidst their excited gabble – they won’t shut up – we decide on our own to go back and search again for a path, but then encounter their father on a horse. He’s drunk but at least points out the gorge we must enter. He says that it’s very steep in there and leaps off his mount to start re-doing Little Scheister’s load. A scuffle ensues. He is hard to deter but I don’t care how many donkey’s he’s packed; I‘m not about to take a lesson in loading from a man who allows his sons to so maltreat their own animals.

In the end the gorge he suggests does indeed get us over the mountains but we realise later that it was still the wrong one. It delivers us to the other side almost a day’s walk too far to the east, yet again lengthening the time it will take to reach our destination. But we’ve camped in another wild valley, melting snow for water over a spluttering fire in the lee of a large boulder while watching the gameplay between a pair of eagles and the marmots whose holes stud the hillside. And the delay also means that we reach spectacular Orto Syrt in the evening rather than morning and so can accept the offer of hospitality from the family that lives there. Getting lost works.

There’s just one more pass to go and it’s snowing again. Perhaps sensing the end is near the donks set a blistering pace for much of the day. We are now operating a new order of march, for in the Naryn valley Little Scheister suddenly went weird on us, repeatedly galloping off until she’d shed her load, which after a week without resupply was almost nothing. She became so unmanageable that at one point I ended up wrestling her to the ground in a headlock and we stayed there until she stopped struggling and I felt that she knew who was boss. We can no longer trust her to follow behind – the much-repaired saddlebags won’t take any more punishment – so have to experiment again. This upsets Tosca who also becomes difficult. As we coax them through the little towns of Jangy Talap and then Ak-Tal it’s as if we are back at day one again. As well as having Ayelen in front to lead Tosca, both donks now need someone behind them, yet if am not immediately behind Tosca she slows down. I cannot be immediately behind them both unless Little Scheister is neck and neck with Tosca but this upsets the latter who veers off to one side, etc., etc., and on, and on. To cap it all, that night I am stung on the hand by a scorpion. Damn this donkey phsychology! I want my camel back! In the end we work it out but essentially it’s fair to say that driving donkeys requires every bit as much concentration as does driving a car. But it still beats carrying your own clobber.

A shepherd gives us tea, bread and jam in his hut near the pass and then we are over the last hurdle. Tash Rabat is almost in sight but first we want to visit Lorbek and Samira (below), the herdsman and his wife who hosted us 3 months ago when hitch-hiking towards China. It’s still a month before they will set up their yurt near the border so they ought to be at home. It entails a punishing day and we arrive in the dark and soaked to the  skin. I have promised the donkeys some of Lorbek’s hay and a space in his barn but it’s his bewildered parents who step outside to investigate what’s set their dogs barking. Our furry porters get a miserable spot next to a cow, fully exposed to the driving sleet and with nothing whatsoever to eat. The men of Lorbek’s family, we learn, take it in turn with their spouses to man this remote spot. The old couple are kind enough to be enthralled by our exploits but with all our soggy kit clogging their tiny home and my rapacious appetite for their bread and cheese we are quite an imposition and don’t hang around in the morning. There’s not even a blade of grass for the donks in any case; their 400 sheep have stripped it down to mud for almost as far as the eye can see.

skin. I have promised the donkeys some of Lorbek’s hay and a space in his barn but it’s his bewildered parents who step outside to investigate what’s set their dogs barking. Our furry porters get a miserable spot next to a cow, fully exposed to the driving sleet and with nothing whatsoever to eat. The men of Lorbek’s family, we learn, take it in turn with their spouses to man this remote spot. The old couple are kind enough to be enthralled by our exploits but with all our soggy kit clogging their tiny home and my rapacious appetite for their bread and cheese we are quite an imposition and don’t hang around in the morning. There’s not even a blade of grass for the donks in any case; their 400 sheep have stripped it down to mud for almost as far as the eye can see.

The last stretch: following sheep trails over a grassy spur we drop into a narrow valley that in the days of the Silk Road was a key route into China. When conditions allowed travellers over the precipitous pass at its head this valley cut almost a week off the normal journey time to Kashgar and beyond. We only follow its winding course for fifteen kilometres and for the most part walk into driving snow and sleet. It settles into our clothes and the wind bites through. We are almost at the end and all four of us just put our heads down and march. I imagine my own cries of encouragement are those of the Silk Road camel and mule drivers and that we are just a tiny fragment in a long, winding baggage train of weary animals and men. Relieved on the Mediterranean shore of their loads of silk and jade the donks would be carrying woollen goods and glass back to China. Those men must have been unbelievably tough, making that journey again and again, fighting off Turcoman slavers and other marauders while dealing with the monstrous logistics of keeping hundreds of animals fed over thousands of miles of desert and high mountains. As they slogged up this valley, the cliffs echoing their shouts and the cracking whips, they must have had a song in their hearts though, for just around a few more corners they would know the caravanserai of Tash Rabat was waiting for them. I know this, because my own heart is singing pretty loudly at this point! It’s shadowy and labyrinthine interior would flicker with the light escaping the low

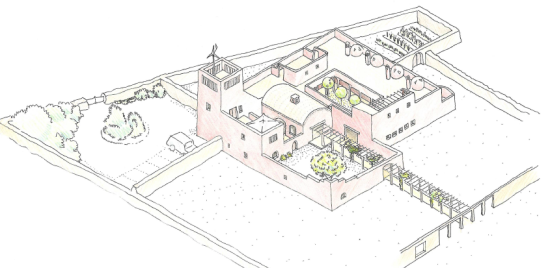

Silk Road was a key route into China. When conditions allowed travellers over the precipitous pass at its head this valley cut almost a week off the normal journey time to Kashgar and beyond. We only follow its winding course for fifteen kilometres and for the most part walk into driving snow and sleet. It settles into our clothes and the wind bites through. We are almost at the end and all four of us just put our heads down and march. I imagine my own cries of encouragement are those of the Silk Road camel and mule drivers and that we are just a tiny fragment in a long, winding baggage train of weary animals and men. Relieved on the Mediterranean shore of their loads of silk and jade the donks would be carrying woollen goods and glass back to China. Those men must have been unbelievably tough, making that journey again and again, fighting off Turcoman slavers and other marauders while dealing with the monstrous logistics of keeping hundreds of animals fed over thousands of miles of desert and high mountains. As they slogged up this valley, the cliffs echoing their shouts and the cracking whips, they must have had a song in their hearts though, for just around a few more corners they would know the caravanserai of Tash Rabat was waiting for them. I know this, because my own heart is singing pretty loudly at this point! It’s shadowy and labyrinthine interior would flicker with the light escaping the low  passageways into it’s 30 domed rooms, each having a fire in the middle. Men would be shown their quarters for the night before making their way into the great hall where another central fire, this one huge, would illuminate the throng of travellers seated beneath the ornate plastered alcoves and dome above. Built around 500 years ago it’s an extraordinary building, appearing to grow from the hillside like an outcrop of dark granite; it’s seemingly meagre exterior dimensions diguising a tardis-like complex within. Alone, we explore it for an hour before the cold drives us back to a yurt guesthouse outside.

passageways into it’s 30 domed rooms, each having a fire in the middle. Men would be shown their quarters for the night before making their way into the great hall where another central fire, this one huge, would illuminate the throng of travellers seated beneath the ornate plastered alcoves and dome above. Built around 500 years ago it’s an extraordinary building, appearing to grow from the hillside like an outcrop of dark granite; it’s seemingly meagre exterior dimensions diguising a tardis-like complex within. Alone, we explore it for an hour before the cold drives us back to a yurt guesthouse outside.

Place it next to St Peter’s in Venice, or a similar monument to the 1500s, and Tash Rabat wouldn’t amount to much, yet to me it resonates with it’s past more noisily than any other building I can remember.  Perhaps this is because I can now so easily place myself within its walls in the dying years of the Silk Road five hundred years ago, swapping tales and news with friends and strangers plying the same route. Somehow, not despite the setbacks in China but because of them, Ayelen and I have achieved a closer approximation of what it must have been like to journey through these parts a century or more ago than I ever imagined possible. We’ve walked somewhat less than the 2000kms envisaged – around 1200, we think – but the barriers thrown in our way by local peoples and authorities are really no different to those imposed by the Khans and Emirs of the past. Just as those players of the Great Game I read about as a boy were forced to, we have ducked, dived, dodged and weaved our way elatedly around those barriers or we have waited, bored and frustrated, to learn our fate. Unfortunately we are not to return home with our pockets stuffed with precious jade and silks, but nor have we been beheaded before

Perhaps this is because I can now so easily place myself within its walls in the dying years of the Silk Road five hundred years ago, swapping tales and news with friends and strangers plying the same route. Somehow, not despite the setbacks in China but because of them, Ayelen and I have achieved a closer approximation of what it must have been like to journey through these parts a century or more ago than I ever imagined possible. We’ve walked somewhat less than the 2000kms envisaged – around 1200, we think – but the barriers thrown in our way by local peoples and authorities are really no different to those imposed by the Khans and Emirs of the past. Just as those players of the Great Game I read about as a boy were forced to, we have ducked, dived, dodged and weaved our way elatedly around those barriers or we have waited, bored and frustrated, to learn our fate. Unfortunately we are not to return home with our pockets stuffed with precious jade and silks, but nor have we been beheaded before an indifferent crowd.

an indifferent crowd.

The film I have been trying to make along the way is tentatively entitled, ‘Getting My Wife to Settle Down.’ With so little interaction with the Uighur people recorded, whether or not we have enough interesting footage for a 50-minute film remains to be seen but at least the title subject has been achieved. Ayelen – here having a bad hair month – is as keen to get home as I am and at last there is talk of children.

Postscript: The Donks

We no longer have the time to walk the 65kms to At Bashi to sell the donks so stop at every homestead on the way back down the valley to see if anyone will take them. Nobody is interested but for the Chinese road workers at the bottom so we walk on almost until dark to get as far away from these donkey-munchers as possible. Then we set Grumpy Tosca and Little Scheister free in a grassy valley and set about thumbing a lift back to reality. There’s little traffic on this lonely road so we have plenty of time to watch them drift slowly away from us, grazing contentedly. I have hated them at times, these two little characters, but they have carried my bags and for that I love them. Of course they are completely unaware of the momentous event that has just befallen them and will probably allow themselves to be re-enslaved by the first shepherd who comes along. I only hope he doesn’t sell them to the Chinese.